After the fall of the Roman Empire, Italian art, due to the country’s lack of political unity, was marked by a disunity that favoured the emergence of different artistic languages and local and regional schools. In particular, urban cultures (Florence, Rome, Venice) set the trend in the development of art. Despite all the differences, however, the overarching traditions of the Mediterranean region were preserved. For centuries, Italian art had a decisive influence on all occidental art and culture.

Middle Ages, Pre-Romanesque

Until the 11th century, architecture was characterized by the insistence on Late Antiquity and early Christian traditions, such as the flat-roofed basilica without a transept, with its thin walls, and the Baptisteries, mostly built as central buildings. The first attempts at structuring the space (by means of arcades) were made in Lombardy (core of the Basilica of S. Ambrogio in Milan, 824-859; S. Satiro, Oratory of Ansperto in Milan, 861 to 881). A gradual transition to Romanesque art can be observed from the 11th century to the late Middle Ages. The freestanding bell tower (Campanile in Florence; slate tower of Pisa), vault art, rich structure of front and portal (main works: cathedral in Pisa, San Miniato near Florence, San Ambrogio in Milan) are characteristic for the Italian church building.

Image source: http://www.Panoramaleinwand.net/page/search/tags/Italien

Romanesque

The architecture, although still essentially interspersed with classical elements, was at the same time characterized by several lines of tradition. The cross-domed church of S. Marco in Venice (since 1063), for example, was built under strong Byzantine influence, while the penetration of Byzantine, Islamic and Norman stylistic devices marked the architecture of Tuscany, southern Italy and Sicily. Lombard artists produced the most important Romanesque architectural sculpture (comasks), which was usually integrated into the architectural form in a flat-ornamental manner (Pavia, S. Michele, 1st half of the 12th century). If you are in italy, visit https://www.uffizi.it/.

Takeover of the Gothic period

The French-Gothic architecture received in the 13th century by the Cistercians and later by the mendicant orders of the Franciscans and Dominicans only slowly found its way into architecture, which continued to be oriented towards the continuity of the wall (S. Francesco, Assisi, since 1228), the corporeality of the columns and the emphasis on the horizontal. The vaulted buildings (Arnolfo di Cambio: Florence, Cathedral, 14th century) were characterised by the vastness, clarity and brightness of the rooms. German and French master builders then realised late Gothic style elements at Milan Cathedral; otherwise, however, the Gothic influences remained rather minor.

- In sculpture, on the other hand, Gothic forms were already taken up in the 12th century (B. Antelamis in Parma Cathedral) without abandoning Romanesque and antique stylistic elements.

- The monumental sculpture of N. Pisano, later also that of A. di Cambio, was also based on classical and Romanesque models.

- Other main masters were Fra Guglielmo (San Domenico in Bologna) and especially L. Ghiberti (Doors of the Baptistery) in Florence, who led over to the Renaissance.

The founder of Gothic painting was Giotto di Bondone (frescoes of Assisi), school of Siena and Fra Angelico da Fiesole. Byzantine painting (“maniera greca”) experienced a tremendous upswing around 1300 with the works of Duccio and S. Martini, who worked with Byzantine Gothic influences, Cimabue, who reoriented himself to the early Middle Ages, and Father Cavallini, whose Roman wall paintings revived early Christian traditions. In Giotto’s frescoes (Arena Chapel, Padua, 1305/06), which integrated several stylistic elements, the character of the modern picture of the modern age was revealed, in which reality, bounded by a frame, with monumental figures and a uniform view, revealed itself to the viewer in a realistic way.

Renaissance and Mannerism

The epoch was characterized by the depiction of nature according to scientific rules, in which the aesthetic ideal, modelled on antiquity, was seen in a conscious departure from the “barbaric Middle Ages”.

New Platonism, interpreted from a Christian point of view, was the ideological tool used in architecture to create new sacred buildings. The divine order was to be revealed in the abstract order of numbers and geometric figures (F. Brunelleschi’s Basilica S. Spirito in Florence, 1436 ff.). Lightness and functionality of classical models dominated the Florentine architecture of the early Renaissance. In contrast, the Roman architecture of the High Renaissance (around 1500) was oriented towards the powerful and heroic, which, coupled with rationality, influenced European architecture into the 19th century.

- Examples of these forms of expression of the High Renaissance are Bramante’s Tempietto (S. Pietro in Montorio, 1502), A. da Sangallos’ Palazzo Farnese in Rome (1541 ff.) and Michelangelo’s sketches for Saint Peter.

- Mannerist exaggerations in form and architectural logic can also be seen in Michelangelo after 1520 (Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence, 1530 ff.), but are confronted with classicist answers (A. Palladio’s Villas in Veneto).

In the 15th century, Florentine sculpture, with its freestanding statues oriented towards the ancient image of man, took a different path than the rest of Europe. The spirit of antiquity, reinterpreted, was impressively shown in Donatello’s works (nude statue of Bronze David, Florence, c. 1430; equestrian monument to Gattamelata, Padua, 1447). In the second half of the 15th century, the style of the Florentine Early Renaissance (Ghiberti, the Pollaiuolo brothers, Verrocchio) spread throughout Italy. The unfinished work of Leonardo and Michelangelo documents the search of the Roman High Renaissance for perfection of form. Michelangelo’s David (Florence, 1501) achieved this aesthetic ideal of perfect design, but in his late work it was again relativized in mannerism (Pietà, Florence, Cathedral, 1548-55). Sculptors such as B. Cellini and G. da Bologna turned away from the stylistic means of the Renaissance in the second half of the 16th century and created a mannerist artistic language with expressive forms of representation.

Painting experienced a heyday in the Renaissance, whereby the originally religious panel painting in particular opened up new, profane contents: the portrait by Raphael (“Sistine Madonna”), the landscape by Leonardo, the still life by I. de’ Barbari and Botticelli’s mythologically influenced paintings (“Spring”, “Birth of Venus”). In the linear perspective as a “symbolic form” the way of thinking of the Renaissance, which was committed to rationality and saw man and nature as a harmonious whole in an ideal world oriented towards natural science, became apparent. This attitude becomes particularly clear in the works of Masaccio (Zinsgroschen-Fresko, Brancacci Chapel, Florence, 1427), P. Uccellos, F. Lippis and A. Castagnos. Masaccio and Masolino were the first great masters of the moving act of the early Renaissance. Piero della Francesca and Leonardo’s use of correct colour and air perspectives removed painting from its naturalistic beginnings and breathed atmosphere into it. Light and colour were elevated to the ideal medium, in Venetian painting even to the carrier of visionary representations of Arcadia (Giorgione; Titian’s “Pietà”, 1573-76).

- In the High Renaissance it was possible for a short time to combine classical ideals with scientific experience into a harmonious order, especially in the works of Raphael, Leonardo and Michelangelo.

- The expressive elaboration of individual means of representation in Mannerist painting in Titian, Tintoretto, G. Romano and Bronzio showed the first tendencies of the Baroque.

- The ceiling paintings by Correggio are regarded as the transition from Renaissance to Baroque.

Baroque

Baroque art, which was created in Rome around 1600, continued the ancient tradition of the High Renaissance. It came about, as it were, as a rejection of Mannerism, whose expressive means of expression were taken up by Baroque art.

The architecture was oriented towards the representative and absolute style of representation (large squares, monuments, magnificent staircases such as the Spanish Staircase in Rome by F. de Sanctis). The building of St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, on which Bramante, Michelangelo, Maderno, Borromini and Bernini worked, is a style-historically influential building: The dome (designed by Michelangelo) remained a central moment in the construction of the nave. Characteristic of the architecture of the period were the façades by P. Cortona (S. Maria della Pace, 1656) and Borromini (S. Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, 1667 ff.): they showed a balance of plastic contrasts between column and pilaster, convex and concave, light and shadow. Brilliant architectural space solutions were created by the Baroque architects Bernini (S. Andrea al Quirinale, 1658 ff.) and Borromini (S. Ivo della Sapienza, 1642 to 50). Turin and Venice, along with Rome, were centres of baroque architecture.

In Roman sculpture, G.L. Bernini succeeded in combining architecture and painting by painterly harmonizing the Baroque contrasts of nature and ideal, gravity and movement. In Rome, painting developed between the poles of lively classicism (A. Caraccis’ ceiling paintings in Palazzo Farnese, 1597-1604) and naturalistic simplicity (Caravaggio, conversion of St. Paul, 1600). Through an increase in spatial illusion and colour fastness, ceiling painting experienced a tremendous boom (Domenichino, Lanfranco, P. da Cortona, Pozzo).

18th and 19th centuries

The classicist tradition determined the architecture in Rome (C. Fontana), with the exception of the Spanish Staircase, which was influenced by the Rococo, which played a modest role in Turin, Vittone and Iuvara.

The genres of veduta, landscape and genre painting (Canaletto, Bellotto, F. Guardi) and the religious altarpiece (Piazzetta) were the main influences in Venetian painting. The most important ceiling paintings of the epoch were painted abroad (Tiepolo, Würzburg Residenz, 1750 to 53). Only the sculptures of A. Canova and the paintings of the Florentine Macchiaioli were outstanding in the fine arts.

20th century

Around 1910 Futurism radically broke with the rigid traditions of the 19th century and developed an aggressive language of art. He demanded in the last consequence the destruction of all old and valid values, which drove some of his representatives (among other things F.T. Marinetti) to fascism Mussolini.

The art during fascism was entirely focused on an officially promoted neoclassicism, which was especially true for architecture, which only developed into modern architecture in the 1950s and 1960s (L. Nervi, Sportpalast, Rome, 1958-60; G. Ponti, Pirelliturm in Milan, 1956-59; G. Michelucci, Autobahnkirche near Florence, 1964).

The border between sculpture and painting between abstraction and construction touched L. after 1945. Minguzzi, P. Consagra and L. Fontana with their works. Symbolist ideas (Pittura metafisica by de Chirico and Morandi among others) and expectations for the future (by the Futurists U. Boccioni, C. Carrà) marked the two poles in painting around 1910.

After 1945, the recourse to Neoclassicism (“Novecento”) and Realism (R. Guttuso) was followed by the opening of Italian art to international styles such as abstraction (A. Corpora, A. Magnelli), Pop and Op-Art, and new Realism (G. Baruchello).

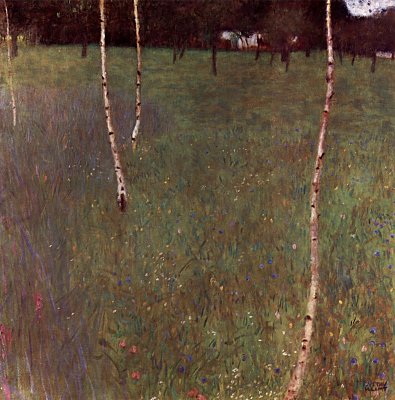

Klimt’s motifs are partly provocatively erotic, partly playfully ornamental. He creates impressive portraits, especially of ladies of the Viennese upper class, but also intensively condensed landscapes. As the darling of certain circles of the Viennese society of the outgoing KuK monarchy, he was able to depict the spirit of the feudal bourgeoisie with its striving for aesthetic cultivation and the desire for increased enjoyment of life in the Fin-de-Siècle like hardly anyone else.

Klimt’s motifs are partly provocatively erotic, partly playfully ornamental. He creates impressive portraits, especially of ladies of the Viennese upper class, but also intensively condensed landscapes. As the darling of certain circles of the Viennese society of the outgoing KuK monarchy, he was able to depict the spirit of the feudal bourgeoisie with its striving for aesthetic cultivation and the desire for increased enjoyment of life in the Fin-de-Siècle like hardly anyone else.

The very fast ones shop their wall decorations on the Internet at providers such as My Poster or Posterlounge. Or they access the poster and art print departments of the furniture stores, as if they were walking by, just like they did before with storage cans, candlesticks and bathroom carpets. On the net as in a furniture store, the buyer finds everything that

The very fast ones shop their wall decorations on the Internet at providers such as My Poster or Posterlounge. Or they access the poster and art print departments of the furniture stores, as if they were walking by, just like they did before with storage cans, candlesticks and bathroom carpets. On the net as in a furniture store, the buyer finds everything that